From Palestine to Paris: The Parisian by Isabella Hammad

Undocumented immigrants in the US, persecuted minorities of Pakistan, people nostalgic for life under tyranny in Eastern Europe, how do we empathize with those who experience such trauma? Journalists tell us what happens to them; poets, artists, and fiction writers make us feel with them. So if you’ve been following the latest news about Palestine, and you want to feel with the people of Palestine, consider reading or listening to Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian.

Hammad is the winner of the 2018 Plimpton Prize for Fiction by the Paris Review, the 2019 O. Henry Prize, and was short-listed for the 2020 Walter Scott Prize of Historical Fiction.

Isabella Hammad

Last year, I reviewed The Parisian for the Daily Times of Pakistan. Today, I am returning to it.

The Parisian from Palestine

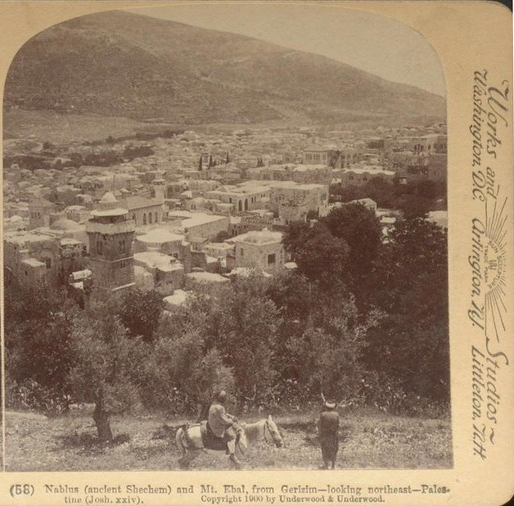

The Parisian is the story of Midhat Kemal, a Palestinian born in Nablus, educated in a private school in Constantinople, a medical student in Montpellier, a flâneur in Paris, and a business man once he returns to his hometown, Nablus.

Author Isabella Hammad’s debut novel The Parisian, the story of Midhat Kemal, will, no doubt, be the next binge-worthy political and family saga on Netflix or Amazon Prime. The characters, themes, and plot of her novel are from the previous century, but are relevant even today. The politics of the Middle East, the conflicts of identity and culture, and the heartbreak that comes with love and relationships are central to the story of Midhat Kemal.

Middhat’s story begins around 1914 and ends just before World War II. To avoid his eldest son’s conscription in the Ottoman army, Midhat’s father, a successful businessperson, sends his son to Montelier, France, to study medicine.

There, Dr Molineau, an anthropologist and his daughter Jeannete host him. He leaves them abruptly after learning that his host is studying him like an organism.

Demeaned by this realization, he moves to Paris where he spends the next four years studying history and politics, and entertaining himself with a range of women.

Midhat acquires a western demeanor

In Paris, Midhat acquires a western demeanor and returns to Nablus, the uncrowned queen of Palestine, to his father’s thriving clothing business. He returns to the British and French manipulations of Palestine, Syria, and the larger conflicts of the Middle East. A reflective young man, Midhat, participates in political discussions with his father and friends, all the while reflecting on his own identity and personal connections. Midhat’s personality is revealed through the women he encounters. His mother dies when he is only two and his paternal grandmother cares for him until he leaves for school in Constantinople (Istanbul).

Early in the story, Midhat muses about himself: “It had never occurred to him before to question why Midhat should be Midhat that no one else should be Midhat, or that Midhat should be no one else.”

Tweet

The pre-teen Midhat in Nablus is besotted by his red-haired Christian neighbor.

And later, as a medical student in Montpellier, France, he is obsessed with Jeannette. This obsession continues for years to come.

Trying to forget Jeannette, Midhat chooses to have short-lived relationships with a range of women in Paris until he returns to Nablus. There his grandmother plans to arrange his marriage at the behest of Midhat’s father.

From the introspective Midhat to his grandmother, Teta, with whom Midhat lives in the family home on Mount Gerizim, all the characters that Hammad creates are like relatives of a large extended family. And we want to get to know them to understand the complexities of their lives.

A story that will stay with readers long after it is over

True to the time and the culture in which she lives, Teta convinces Midhat that a wife will care for him, particularly regarding things that he has never thought about, his clean clothes, his meals. The intermingling of Midhat, Teta, and all the other characters, creates a story that will stay with readers long after it is over. Father Antoine is one such character who is portrayed with the same finesse as Midhat and Teta. Antoine documents all he observes and has a strong bond with Sister Louis, who provides patients who will talk to him and give him information. He relies on her to learn about the town, the people, and himself. He finds Nablus different, with “something strong in the air”. The macrocosm of post-World War I and the end of the Ottoman Empire frames the story of Midhat.

Nationalist movements shape lives

Within this universe, the nationalist movements of Palestine and Syria shape the life of Midhat and those whom he encounters. Hammad then weaves delicate and intricate scenes to embellish her novel with the skill of a miniaturist. Readers thirsting for world history and politics will be satisfied in the coffee houses of Nablus where Midhat and his friends gather to discuss the nationalist movements of the time.

Languages of Palestine

For those looking for a family saga this story that revolves around three generations spanning two continents fulfills that need. In addition, for readers seeking artistic gratification with the intermingling of the beauty of Arabic, French and English, The Parisian will deliver.

Hammad’s second novel is already in the works. No doubt, she will deliver a story of the same caliber. Before that, The Parisian will be picked up as a screenplay.

Create Cultural Memories through Literature and Art

In her interview with Professor Handal, the author elaborates on the autobiographical elements of the story of Midhat, who is based on her grandfather. She talks of ancient city of Nablus and”the soap factories, the old coffee shops, the street vendors”. And of Nablus today, she says, “During the early 2000s, Nablus was ringed with checkpoints and unemployment soared, and economic hardship can do a lot to dampen engagement. But it can also have the opposite effect, as we have seen elsewhere.”

Sounds like a fascinating book. I’d like to read it.

It is. I listened to it on audible and loved it.